Opponents of the mining industry – such as protestors who disrupted the International Mining and Resources Conference in Melbourne in 2019, just months before COVID ceased all such events — fail to understand the vast amounts of metals and minerals needed for everyday items.

More than 40 mined metals and rare earths are used to produce a single smartphone; there’s salt in detergents, iodine in disinfectants, zinc in soap; silicon, phosphorous, antimony, boron, and tantalum in computer processes.

And those demands are without considering the copper, nickel, zinc, critical minerals, and rare earths required for renewable energy generation including solar, wind, and battery storage, and the electricity infrastructure required to transmit the power these projects produce.

The International Energy Agency quantified the size of just part of the challenge in an assessment of the battery supply chain, saying global battery and minerals supply chains needed to expand ten-fold to meet projected critical minerals needs by 2030.

Under various scenarios, that translated to the need for 50 new lithium mines, 60 nickel mines, and 17 cobalt mines.

Not surprisingly, exploration companies understand the challenge.

Figures released by the State Government in October revealed that in the latest round of Exploration Inventive Scheme funding there was a significant increase in the search for battery minerals, driven by nickel.

Mines Minister Bill Johnston said the global transition to green energy continued to drive the search for minerals in Western Australia.

None of this will come as a surprise to those involved in the resources sector and yet mining retains a reputation for being part of the environmental problem, rather than part of the answer.

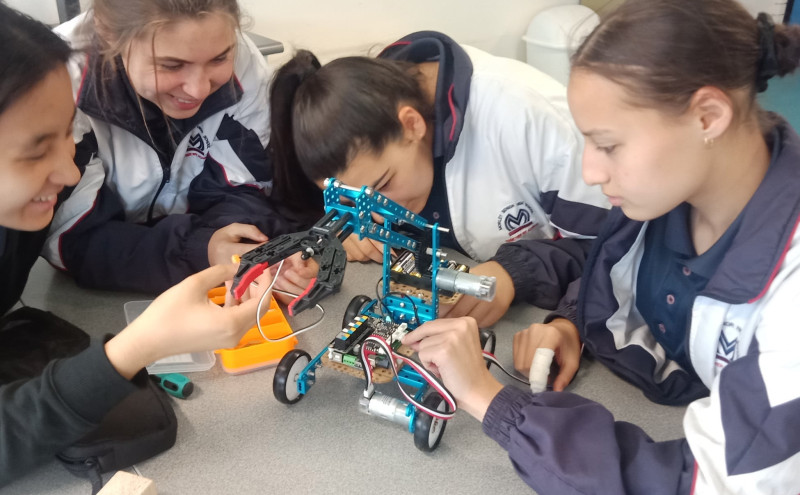

And those negative perceptions are flowing through to the employment choices of the next generation of potential workers, who are opting for other jobs at a time when the sector needs them the most.

The resources sector must do a better job of defending its reputation, presenting the societal and environmental value propositions of increased mining, in sustainable ways, if it hopes to attract workers to take up traditional and emerging jobs.

And the task of attracting women to the sector has become even more difficult after the harrowing truth of sexual assault was exposed by a Parliamentary inquiry.

To its credit, the sector is responding forcefully. But trust is easy to lose and hard to win back.

The basic tenant of stakeholder engagement is engage early and engage often.

For the resources sector, this means at each level of education, from primary schools through to universities, creating a sense of excitement and achievement in working in the resources sector.

Federal Minister for Resources Madeleine King addressed these issues in a wide-ranging speech to the WA Chamber of Commerce and Industry in October in which she challenged the sector to do more to tell its story and find innovative ways to engage with those who will comprise a future workforce.

“Some Australians remain unaware of how the resources industry is improving their lives – whether it is providing ore for wind turbines for green energy or lithium for that mobile phone to allow them to share a TikTok clip,” Minister King said.

“We need to get the message out more effectively – resources not only enable Australia’s standard of living, they are the key to a clean energy future.

“As I have said many times in recent months – without the resources sector there is no net zero.

“We all know the resources workforce is already stretched and there is a major problem in attracting and retaining skilled workers.

“A big barrier to attracting these workers is the attitude many young Australians hold towards the resources industry.

“Enrolments in relevant degrees are dwindling, making it even harder to find qualified staff in this time of skills shortages.

“We need to be able to convince more young people and more women that attractive careers can be found in the sector. Workplaces need to be made safer and more welcoming.

“It is up to the industry to turn the poor perceptions around. It has the capacity to do so. Poor perceptions can be replaced by positive ones. I am keen to work with industry to help make this happen.

“So how do we get that young person on TikTok to make the link between their new iPhone and the resources industry?

“I think the resources industry needs to get more creative in how it connects with young people.

“Perhaps you need to organise a national computer gaming competition?

“Miners for Minecraft maybe?

“I confess I have dabbled in Minecraft myself.

“And anyone who plays Minecraft knows that before building your palace you first need to find some iron ore, build a furnace, then find some coal to smelt your iron ore to turn it into steel.

“Surely we can turn the Minecraft-crazed kids of today into the skilled staff the resources industry needs for tomorrow?

“More seriously, there is an immediate need to target the skills that are in demand such as mining engineers, electricians, plumbers, and mechanics, but we must also plan for the future of work.”

Minister King said the key themes raised by participants at a series of roundtable meetings in Brisbane, Perth, Kwinana, and Karratha and shared at the National Jobs and Skills Summit in September, included the need for stronger industry links with the university sector.

Just as there are challenges and opportunities in the mines of the future, there are challenges and opportunities in finding the workforce of the future.

There is no time to lose for both.